As the market for carbon credits continues to grow, it’s essential that we bring biodiversity “along for the ride,” not just because it’s the right thing to do but because biodiversity underpins all other ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration. The voluntary carbon market is currently under a lot of scrutiny around how much real climate benefit it is delivering, but another issue is brewing – carbon projects’ impacts to biodiversity.

While some carbon projects claim to benefit biodiversity, few have actually quantified their impacts beyond a simple, qualitative effort, making it impossible for market forces to reward carbon projects that have greater benefits for biodiversity. And some carbon projects are almost certainly bad for biodiversity (think non-native monocultures of trees planted in native grasslands, for example), but these projects are not penalized in the market, at least so far.

What’s the answer? Rigorous, quantitative measures of the impacts of carbon projects on biodiversity, both good and bad. While this will be a new area of expertise for many carbon developers, the talent pool is out there and ready to get to work (just ask any recent PhD in wildlife ecology if they’d be interested, and you’ll likely hear “yes”).

Once carbon credits each come with an estimate of their impacts to biodiversity, carbon buyers can choose to buy credits that create more biodiversity, and carbon developers can modify their carbon programs to generate more benefits to biodiversity.

Ecosystems are carbon sinks

Think of an ecosystem as a tall, sturdy stone tower — an elegant, complex, interconnected stack of biodiversity blocks, with each block a species of plant, animal or microbe, connected to others by the mortar of their interactions in their shared landscape. You might not really notice taking away one block, but knock out more blocks and pretty soon the wind is whistling through the building and water’s pooling on the floor. Remove enough blocks and the whole tower comes tumbling down, with us inside it.

Without biodiversity — the many diverse forms of life on earth, from microbes to mushrooms to towering redwood trees and thundering herds of wildebeest — there’s no viable way to meet our climate goals because ecosystems are critical carbon sinks. There’s also no scalable way to get clean water, clean air, pollination for our crops, or habitat for wildlife without it. It underpins every other ecosystem service we depend on.

But so far, we haven’t done enough to make sure that biodiversity is protected and restored, leading to our current biodiversity crisis. And until positive impact for biodiversity is measured and valued by markets, biodiversity loss will continue.

Carbon markets and biodiversity

Because biodiversity underpins the function of nature-based solutions (NBS) to climate change, NBS have huge potential to help solve the biodiversity crisis. Many environmental NGOs have supported this position, and the voluntary carbon market has responded, resulting in biodiversity emerging as a key indicator of carbon quality, alongside benefits to local communities and other co-benefits.

But so far, almost no carbon projects deliver credits with quantified biodiversity impacts reported. The uncomfortable truth is that not all carbon projects are equal in terms of their impacts to biodiversity. Indeed, maximizing carbon while ignoring biodiversity could lead to some very negative outcomes: actions like planting non-native trees in native grasslands, or incentivizing fast-growing monocultures over multi-species polycultures in working forests can lead to rapid carbon sequestration, for a while. Projects built on this carbon “tunnel vision” will undermine biodiversity, which in turn threatens long-term carbon sequestration as disease, fire, and other disturbances sweep through these poorly-functioning and simplified ecosystems.

Developers that do report on biodiversity typically take a shortcut approach, resulting in biodiversity being a “checkbox” co-benefit to buyers. These shortcuts involve a lot of assumptions; for example, that more native vegetation is a good proxy for high-quality habitat for multiple species, or that a project that overlaps with the global ranges of rare or sensitive species means that those species occur within the project boundaries or benefit from the project’s actions.

Using shortcuts makes a lot of sense when quantitative approaches just aren’t possible or feasible, but a lot is lost in the process. Market-based mechanisms need quantitative measurements of impact to work, with a variable amount of biodiversity per credit. Without quantified measurements, buyers can’t distinguish among credits that produce a little or a lot of biodiversity benefit. As a result, projects that produce more benefit cannot be rewarded, and developers are not incentivized to improve their biodiversity metrics, so the virtuous cycle that markets can produce, at their best, has not started for biodiversity that accompanies carbon projects.

Going beyond the checkbox approach to biodiversity co-benefits

Luckily, we are living in a golden age for measurement and modeling of biodiversity. Rapid progress is happening in field-based data collection tools, remote sensing of habitat attributes, and computing power and modeling approaches. This means we can now move towards quantitative models of biodiversity additionality for carbon credits. Carbon projects with the most benefits to biodiversity can be rewarded, and projects that damage biodiversity can be identified and fixed.

Responsibility for making quantitative biodiversity co-benefits a reality is shared across the carbon crediting space. Developers should work to quantify biodiversity rather than using shortcuts. This will mean employing internal staff or external consultants with deep expertise in biodiversity measurement and modeling. On the other side of the marketplace, buyers can require more than a “checkbox” for a biodiversity co-benefit, and ask for a quantified amount of benefit, with realistic baselines, uncertainty, and additionality demonstrated.

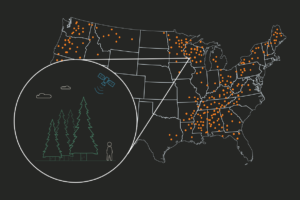

As a first step, NCX is working to measure the impacts of our forest carbon program on biodiversity. Starting with birds that nest in landscapes across the Southern United States, we’re developing multi-species models of habitat quality for the entire bird community, so that trade-offs between species and their habitat needs are incorporated into our carbon models. The lessons we learn will allow us to improve our forest carbon program so that it yields more benefits for birds, and also to grow our biodiversity modeling expertise so we can start to consider other species across the forest ecosystems we work in, like bats, terrestrial mammals, and more.

We know we can’t do this alone —we’ll need others to join us on this journey if we truly want to put carbon markets to work for biodiversity. Are you looking to get involved in data sharing, method development, certification approaches, or investment into biodiversity projects? Reach out to science@ncx.com.

Want to learn more?

Continue the conversation by registering for our upcoming webinar, The Path to Nature Positive Carbon Credits Starts with Better Measurement, on January 25, 2023 at 1:00 p.m. EDT.