Are carbon credits a good revenue stream for your land? To make an informed decision, you’ll need to understand what a carbon credit is and how many credits your land can produce.

A carbon credit is used to pay a carbon debt. Over the past decade, companies have begun tracking the carbon that they emit into the atmosphere. Every ton of carbon that they put into the air adds to their carbon debt.

A carbon credit represents one ton of CO2 kept out of the atmosphere for a period of time. By purchasing enough carbon credits, a company can cancel out its carbon debts. This allows them to make claims like, “we’re a carbon-neutral business” which can be attractive to consumers, employees, and investors.

In 2023, companies bought over $1 billion worth of carbon credits. For comparison, the amount paid for all the timber harvested in the US each year is about $10 billion, so carbon is becoming a significant economic driver for forest management.

“Nature-based solutions” like forests and soils are a major source of carbon credits. How many carbon credits can your land produce? It depends on how much more carbon your land can hold out of the atmosphere over some period of time (usually 40+ years) than it would “normally.”

For example, if you own a forest, the number of carbon credits your land can produce is determined by three factors:

- carbon stock

- “baseline” forecast

- term length

Carbon Stock

The amount of carbon contained in your trees is known as the “carbon stock.” You might also hear this referred to as “biomass.” Most forest carbon programs only count the carbon in “aboveground biomass” which is the carbon in the trunk and limbs but not the carbon in the roots and the soil.

For reference, a pine tree that is 12 inches in diameter (as big around as a medium pizza) contains roughly 1.5 metric tons of “carbon” from a crediting standpoint. A normal passenger car emits about 3 times that amount each year.

The carbon stock on your land can change for a few reasons:

- Planting – adding new trees to your property increases biomass as they grow

- Growth – every year your existing trees get bigger and add more biomass

- Harvests – if you cut down your trees, you temporarily reduce the biomass on your property

- Natural Disturbances – hurricanes, fires, pest infestations, and more can kill trees and reduce the carbon stock

Baseline Forecast

One of the trickiest parts of carbon credits is the “baseline” forecast. This is a forecast of what your forest would look like under a baseline or “business as usual” scenario during the term of the carbon program. The difference between your actual carbon stocking and the forecast determines the number of carbon credits you produce.

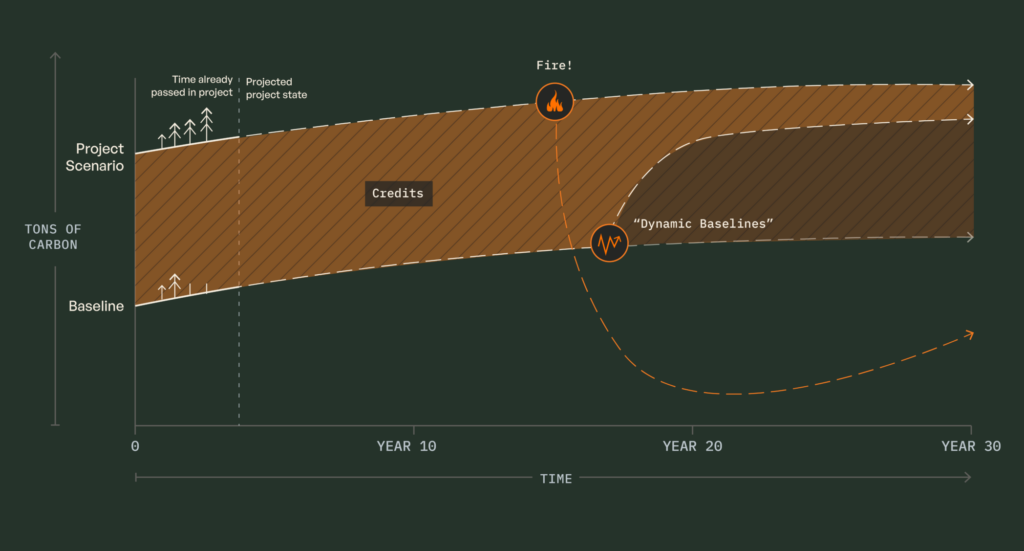

Caption: Carbon credits are the difference between your carbon stock and your baseline – both of which can change over time in unexpected ways.

How are baselines determined? You might be surprised to learn that this is a highly disputed issue, and experts disagree about what constitutes a “good” baseline. In fact, these disagreements are at the heart of much of the recent bad press about carbon credits.

Currently, different forest carbon programs take different approaches to setting baselines at the start of a project:

- Regional baseline – compares your property to the “average” property in your state or region

- Neighbor baselines – compares your property to “similar” properties based on size, forest composition, past behavior, etc.

- Economic baselines – models out the optimal economic management of your property without carbon revenue. This analysis may be supported by a documented forest management plan and management history.

One emerging trend is the use of “dynamic baselines” that don’t make a forecast of how your land will be managed at the start of a project, but instead compare your property to similar places at regular intervals and issue credits based on how your carbon storage compares to your neighbors. However, landowners need to be aware of the risk that a shifting baseline could significantly impact the number of credits their land generates.

Term Length

Another factor to consider is the duration of the forest carbon program. There are a variety of contract term lengths currently available in the market: 10, 20, 40, and 100 years. However, some programs limit your land’s eligibility for other programs for far longer. For example, some programs require a permanent conservation easement that restricts your land management in perpetuity. It’s extremely important to understand if there are any encumbrances to your land that outlast the nominal term of the carbon program.

The term length has a direct bearing on your potential rate of return and your opportunity cost for pursuing other land management options. Longer terms can also mean more risk for you as a landowner. Who is liable if the forest burns down during the contract period? Is your payment in jeopardy if the price of carbon drops? If the baseline changes? Understanding the time aspect of a carbon program is a key part of making an informed decision about the right programs for you and your land.

This article is the first in a series that NCX is publishing to help landowners make informed decisions about carbon programs. Stay tuned for future posts on our blog. In the meantime, create a free account at NCX.com to explore a wide variety of carbon and other natural capital programs for your land.