Land Rooted in History

“This is our piece of the earth.” Gayle and her siblings recall their father, Dewey Townsend, telling them this throughout their childhood in Spring Hill, Mississippi. The Townsend Family has owned their land in Mississippi on their paternal side since the Reconstruction period after the US Civil War, with deeds dating back to the 1870s. Their great-grandmother, Mary “Mollie” Dunn, an ex-slave and daughter of a slave owner, received land from her father, beginning their long and exceptional story. Land ownership for the Townsend-Shelton family has always represented more than just equity in a physical asset that can be used to produce crops, cattle, dairy, and timber. It has represented economic opportunity, freedom, resilience, and the ability to forge better futures for their children. Their story has changed over the generations as has the land, but their commitment to generational stewardship has never faltered.

Multiple generations of Gayle’s family photographed on their land.

Building for the Future

The Townsend family’s land wasn’t just a farm; it was the heart of a thriving, self-sustaining community. Unlike many areas in the South following the end of the Civil War that were predominantly managed through sharecropping agreements, the Spring Hill community was a center of Black land ownership. At its peak before the great migration of the 1950s, when many families fled to large cities in the north to find work in factories, Spring Hill was roughly 35 square miles of land, inhabited by 75 families (60 of whom directly owned and managed the land). All the families were farmers. The Townsend Family saw early on that protecting their land and maximizing its use not only supported their family but created opportunities for the broader community. They grew crops, raised cattle, milled lumber and eventually built and owned a cotton gin, blacksmith shop, a dairy, and grist mill. They also opened a general store in the community, which provided easy access to important resources. This economic activity created jobs for local community members and eventually attracted investment from other businesses to the area.

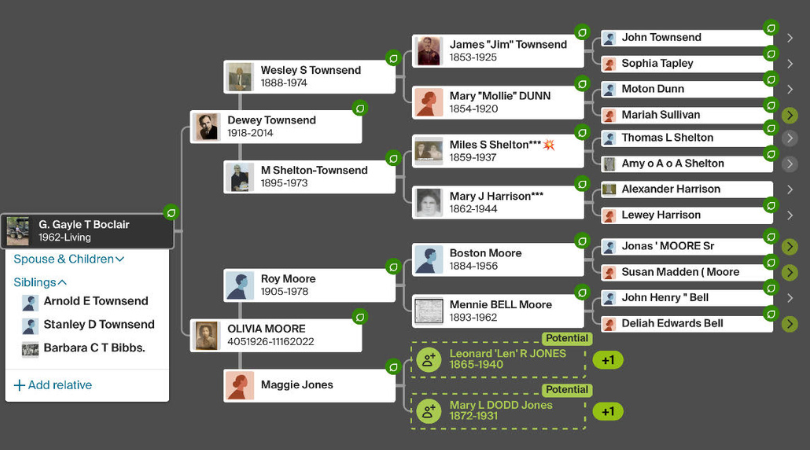

Gayle’s family tree going back to the early 1800s

Land as Opportunity

Early on, the Spring Hill community recognized education as the true path to freedom. Education meant becoming competent in reading, writing, math, and knowledge about agriculture so that they could support and protect their land in the face of any threat and capitalize on new opportunities when they appeared. They built the Spring Hill School and Church with other parents in the community in 1870. The land the school was on was sold to the church by the original owner, which will be important to remember later in this story. The school was an accredited institution that eventually expanded in 1928 to include grades 1 through 9. Recognizing the opportunity to attract higher quality teachers through the Vocational Agricultural Teacher program possible under the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917, they brought in a reputable vocational agricultural teacher who worked within the community to help all the landowners increase their yields of cotton, corn, and hog and cattle production. During this time, the community adopted a progressive “live-at-home” program with an emphasis on creating self-sustaining food systems for the families and broader community. Knowledge about how to use the land for its highest and best use had never been more powerful. In 1936, the school expanded again to support grades 1-12. The community members had to pay tuition to support the operational expenses of the school because Montgomery County would not provide an eight-month school term for black children at the time. The school became a beacon of hope, proving that knowledge and informed land ownership were key to standing up to oppression. Their father, Dewey, was one of 5 graduates in the first graduating class of Spring Hill High School in 1938 who all attended Alcorn A&M College. While studying for his degree, he was drafted and served in France during World War II and was a part of the U.S. operation on D-Day.

Dewey Townsend photographed in his military uniform

After serving in WWII from 1941-1945, Dewey went on to finish his schooling at Alcorn State University and received a graduate degree from Tuskegee University. During this period of transition after the war, he worked a short time in an automotive factory in Pontiac, Michigan where he met his soon-to-be wife Olivia, whom he married in 1947. They decided to return to Spring Hill to help manage the land, the school, and the challenges it faced. Despite legal and societal pressures put forth throughout the Jim Crow era, the Townsends remained committed to their community and their land. Following the Mississippi Minimum School Foundation Act of 1954, there was a required consolidation of all schools in the district. This resulted in a move of the Spring Hill School to Kilmichael, MS in 1960. The new, all white school board had deeded the rights to the land the school was previously on and opened an auction to sell the land. Dewey bought the 16 acres of land in the auction, which are still a part of their family’s roughly 350-acre property today. His commitment to the community did not falter through these changes. He became the first principal of the new integrated school located in Kilmichael in 1960. He was one of many Spring Hill graduates who went on to create a legacy of impact in Mississippi and beyond.

Spring Hill School Students in front of the historic school house

Dewey was increasingly an integral part of the community over the years, eventually becoming the first African-American member of the Board of Alderman at large for the city of Winona for 14 years, Vice President of the Economic Development Council, President of the Montgomery Retired Teachers Association, member of the Zoning Board for the City of Winona, Montgomery County Forestry Association member, Tom Dulin Foundation member, member of Headstart which was the first anti-poverty community action program, member of the Advisory Council for Mental Health, member of the Historic Preservation Commission, member of the Arts Council, Chairman of Board of Directors and Treasurer for the Zion District Association, board member for Habitat for Humanity, and member of the Leadership Committee. He and his wife Olivia were always looking for ways to improve the land and help the community. Dewey Townsend passed away in 2014 at 96 years old, and Olivia passed in 2022, also at age 96. Both of them helped catalogue and share these important historical archives of Spring Hill and the community that built it.

The Next Generation

For this family, the land represents more than a connection to the past, it’s a promise for the future. When the siblings were old enough to start getting involved in the family business, Dewey called them all together to sit down in their parent’s bedroom and tell them how he wanted the assets to be managed. It was a pivotal moment for them. The transfer of knowledge about family land often gets lost as management moves from one generation to the next. Dewey Townsend had worked so hard to build and protect his family legacy, he did everything he could to ensure his children could take the reins with confidence. Managing the land using new technology will help the family better understand their land, their opportunities, and the modern threats that they are faced with. The family has worked closely with NCX to get the full picture of what the future holds for their land and how they can manage it to create financial and environmental wealth.

They envision a “turnkey operation” that future generations can manage sustainably, preserving both the land and its rich history. This means an ironclad legal structure, diverse income streams, a plan to improve the land’s value, a threat mitigation strategy, and a team of experts they trust to keep them updated on changes. The family has worked actively with NCX to analyze all of the income opportunities their land is eligible for and the most attractive cost share programs available through the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) to determine the right path forward. NCX is now helping the family explore ways to optimally “stack” programs and land improvements on the land to achieve their goals.

Shelton Family Reunion 2019 Duck Hill, MS

Land as Legacy

For many families like Gayle and her siblings, their land is a core part of their identity. Their “piece of the earth”, as their father described it, connects their children and grandchildren to the history of their family. It represents the work of generations to create self-sufficiency and opportunities for their children. It represents their connection to their community and the economic engine that drives it. It represents big and small moments spent with loved ones out in the forest and fields. Families change, though, and while some of the challenges and opportunities facing private landowners like the Townsends are the same, many are new. Pressure to sell or develop the land comes from all directions and it can be hard to know who to trust. Threats from pests, pathogens, and natural disasters pose increasing risks for landowners simply trying to pay their property taxes. More diverse economic opportunities through markets for carbon, timber, wildlife habitat, solar energy, and more are all competing for acreage and attention. Making sense of this can feel like a full time job. NCX is proud to work with this amazing family to help them navigate these options with confidence. If you need help thinking about the threats and opportunities your land is faced with and how to find a path forward to reach your goals, create a free account at ncx.com.

All historical information provided by Gayle Townsend Boclair from the archive of Dewey/Olivia Townsend. with supplemental information from Winona Times, Ancestry.com, and other historical documentation from Spring Hill MB Church and school community records.