It’s time to improve forest carbon

Forests can and must be a key part of the climate solution in this critical decade. But recent articles from ProPublica (here and here) and Bloomberg (here and here) have highlighted how many forest carbon projects, despite following the rules, have received millions of dollars while failing to deliver real climate impact. The forest carbon community cannot ignore the inconvenient truths raised by these articles. Instead, we need to rise to the moment and measurably improve the quality of forest carbon projects. Over the last decade, the forest carbon community has learned a lot from these initial groundbreaking projects. Now that we know better, we can – and must – do better.

I’ve seen the problems with these legacy forest carbon projects firsthand. In over a decade as a professional forester, I’ve worked all over the world helping to measure and manage forests. For many of the early forest carbon projects, I was called in as a forest measurement expert. Over and over again, I saw forest carbon projects that didn’t change the landowner’s timber harvest plans. If these projects weren’t changing the harvest plan, what were the landowners getting paid for?

A recent ProPublica article traces this problem with “additionality” back to simplistic carbon accounting rules that use coarse regional averages as baselines. No one in the forest industry buys timber based on coarse regional averages, so why would we buy carbon that way?

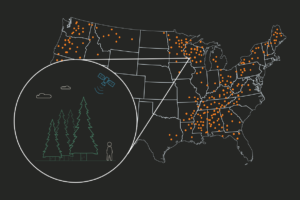

Every acre of forest is unique. Indeed, much of the centuries-old profession of forestry is about understanding the ecology and getting the economics right for each unique acre of forest. You can only manage what you measure, so one of the classic challenges of forestry has always been getting reliable data for each acre of large and complex forests. Thanks to recent advances in remote sensing and computer technology, it’s now possible to actually measure every acre of forest every year.

Acre-level accounting is the key to improving the quality of forest carbon credits. Over a year ago, I published a white paper on forest carbon economics that foreshadowed these recent articles about “subprime” forest carbon credits and pointed towards a solution.

The next generation of forest carbon methodologies must set the correct acre-level incentives for project developers to ensure forest carbon payments drive real climate outcomes.

Rather than vilifying the original work of early forest carbon projects, we should be grateful for what they have taught us. As Maya Angelou said: “I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.”

Now that we know better, it’s time to do better. Here’s what that should look like:

- Update methodologies to use acre-level baselines to better assess additionality

- Stop developing new projects with flawed methodologies

- Stop creating new methodologies with these same flaws.

Climate complacency is not an option. This is a critical decade for the climate, and we are all accountable. We call on the forest carbon community – carbon buyers, brokers, standards bodies, project developers, foresters, landowners, NGO’s, policymakers, and researchers – to join us in pushing for higher standards, quantifiable improvement, and measurable climate impact.