This article was first published in the “Biometrics Bits” column of the September 2020 issue of the Forestry Source.

Measurements Make Markets

Measurements make markets, but confusion around carbon accounting is holding back the development of large-scale carbon markets in the US. In this Biometrics Bits article, we’ll explain how carbon gets measured and we’ll get you up to speed on the basics of forest carbon economics.

Forests are valuable for more than just timber. Wildlife habitat, water filtration, carbon storage, and erosion prevention are just a few of the valuable ecosystem services that forests provide. The value of ecosystem services from American forests has been estimated to be in the tens of billions of dollars annually. Yet timber has been the major historic driver of forest management in the US because markets are underdeveloped for these other ecosystem services.

Emerging ecosystem services markets are beginning to address this market failure. The largest so far is the California Air Resources Board regulatory forest carbon market where forest owners can receive payments for the carbon stored in their trees. Voluntary carbon markets are also on the rise – scarcely a week goes by without another Fortune 500 company announcing a carbon neutrality commitment. As foresters, we need to be aware of these emerging non-timber markets and consider adapting our management to take advantage of these new sources of revenue.

Yet these are still early days, even in carbon markets. The most basic “plumbing” of these markets is fairly clunky, as any forester who has attempted to get a forest carbon project through the certification process could tell you. Part of the reason why this is so hard is because ecosystem services are much more difficult to measure than timber.

Measuring Timber vs. Measuring Carbon Storage

One of the main reasons timber markets work is because it is easy to measure and pay for value – you can directly weigh or scale it! When a logging truck rolls across a scale, you get paid by the ton and then you’re done. It’s a one-time event.

Ecosystem services like carbon, on the other hand, are a lot harder to measure. They take place out in the woods, where measurements aren’t nearly as simple as driving onto a scale. It’s not a one-time delivery of a physical commodity. Ecosystem services are also just that – SERVICES provided over TIME.

All of this means that we need a new framework for thinking about measuring and paying for ecosystem services like carbon sequestration. The three pillars of this framework are additionality, leakage, and duration.

Additionality

Last year, US forests pulled hundreds of millions of tons of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. Even in the absence of large-scale markets for forest carbon, US forests have had a positive growth-to-drain ratio for decades.

Paying landowners can potentially increase the amount of carbon stored in forests even further. However, carbon buyers don’t want to pay landowners to do what they were going to do anyways. In other words, there’s not much value in paying someone to promise not to harvest timber they weren’t planning to harvest. Carbon buyers only want to pay for “additional” carbon above and beyond the landowner’s “business as usual” (BAU) harvest behavior.

This means that assessing BAU carbon stocking for a property is an essential part of determining the additionality of a forest carbon project. As foresters, we understand that the BAU for any given stand depends on many detailed factors. Indeed, the entire sub-field of timber harvest scheduling exists to optimize forest management based on the unique biological, logistical, and economic characteristics of every acre.

However, the California forest carbon market currently has very unsophisticated BAU assessments. Rather than modeling the acre or stand-level timber economics on a particular property, the California rules use a coarse regional average.

In practical terms, this means that properties that already happen to be managed at stocking levels higher than the regional BAU can receive credit for “additional” carbon. This is a windfall for those managers who receive payment without needing to change their harvest behavior, but ultimately results in disappointed buyers who had expected their payments to create real change. Unsurprisingly, a small industry has sprung up to exploit this loophole. The California rules have come under increasing criticism for this deficiency and it is likely that carbon buyers will increasingly demand better assessments of BAU and additionality.

Leakage

Once the additionality of a forest carbon project has been demonstrated, “leakage” is next. Simply put, “If I pay you to defer timber harvests on your property, does that just get balanced out by your neighbor harvesting more?”

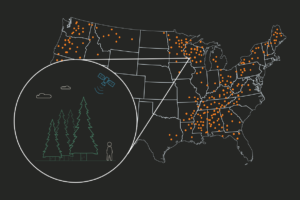

This issue is particularly pronounced when not all landowners can participate in forest carbon projects. Because of high setup costs ($200,000 isn’t unusual) and 100 year commitment periods, only a very small number of very large landowners can participate in the California forest carbon market. Because millions of small landowners are excluded, California forest carbon projects “leak” timber harvest onto neighboring smaller properties. These projects have to take an explicit “leakage deduction” that reduces the amount of carbon credits generated.

There are a number of programs that are making progress towards making ALL forested acres eligible for forest carbon projects. If these programs succeed, leakage will be significantly reduced.

Duration

One of the trickiest issues about accounting for ecosystem services has to do with duration. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, ecosystem services are provided over some period of time.

Different carbon markets have different duration requirements for forest carbon projects. California requires a contract for 100 years. Even voluntary carbon markets often require 40 year terms. These long term lengths stretch for decades in an attempt to reflect a “permanent” sequestration of carbon, but they also discourage landowners from participating. After all, when was the last time you signed a 100 year contract? Furthermore, as foresters we know that there is no such thing as “permanence” in forest systems.

Yet this is also an area where change is beginning to occur. One recent development in carbon accounting is the introduction of much shorter, 1 year contracts for carbon sequestration. These 1-year carbon “rental” contracts are a natural fit with the annual forest management decision cycle. These 1-year contracts can be bundled to achieve an equivalent climate impact as the conventional 100-year term forest carbon projects, but are much easier for landowners to commit to.

Our Profession

The profession of forestry seeks to balance a constantly evolving natural, social, and economic environment. Our generation of foresters finds itself in the midst of major changes in all three of these areas. We must rise to the challenge of delivering the ecosystem services that our society increasingly demands. Because credible measurements must underpin any market in ecosystem services, forest biometricians have an especially important role to play.

As foresters, we have an ethical obligation to help ensure that buyers of ecosystem services get what they pay for. Ecosystem services are by their very nature much more difficult to measure than timber, and there is the potential for buyers to feel cheated if they discover that the services they paid for were illusory. Some are already calling foul – witness the MIT Tech Review’s 2019 article, “Landowners are earning millions for carbon cuts that may not occur.”

This is a new and exciting field where the rules are still being written. The forestry community has a valuable contribution to make to this discussion and our experience can help inform an ecosystem services market that works for both landowners and society at large. If we succeed, foresters will play a key role in addressing some of the most important challenges of our generation and can unlock tens of billions of dollars of value for the society we serve.